5 Facts That Show How Arthur Ashe Transcended Tennis

Newspaper reports from 1968 kept the public on edge with daily, vivid accounts of the fear, havoc, and civil unrest that plagued the United States. Most headlines surrounded the assassinations of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and Senator Robert F. Kennedy. Appalling stories arose from the urban riots that raged in 130 major American cities, including police and prison riots. Anti-war and civil rights protests were in full swing, the space race was a source of extreme tension, and the controversial war in Vietnam raged on. All of this bad news brought fear, anger, and sorrow to the people.

Despite all the noise, a shy, African-American tennis player in big glasses named Arthur Ashe began drawing notice. Ashe was climbing the amateur ranks, knocking aside obstacles, breaking racial barriers, and playing some spectacular rounds of tennis. Here’s how this young tennis sensation affected everything from sports, to the Civil Rights movement…

Rising Star

Arthur Ashe was born in Richmond, Virginia on July 10, 1943. His beloved and doting mother passed at the age of 27, when Ashe was just six years old. This caused his father to tighten the reigns on his and his younger brother’s activities. Arthur Ashe, Sr. strove to make sure his boys attended church and stayed out of trouble in the absence of their mother’s guidance. Ashe, Jr. developed a strong sense of discipline. He graduated top of his high school class, was the first in his family to graduate college, and eventually joined the military. His passionate, steady disposition was also shown in his love of and proficiency for sports, especially tennis.

Arthur eventually caught the attention of national tennis champion Ronald Charity, who coached Ashe to help improve his form. As Ashe began showing even greater talent and the tenacity to work hard on his game, Charity introduced him to Dr. Walter Johnson, who coached Althea Gibson. Johnson would become Ashe’s lifelong coach, mentor, and friend. Johnson would also teach Ashe to fight uncivil and discourteous treatment with politeness, letting his racket game speak for him.

The Long And Winding Road

Tennis forerunners who achieved African-American firsts included:

- Lucy Diggs Slowe, the first female African-American national champion (1917)

- Lorraine Williams, USLTA national champion (1953)

- Althea Gibson, 11-time Grand Slam champion in French Open (1956), Wimbledon (1957, 1958), and United States Open (1957, 1958)

- Bob Ryland, male tennis professional (1959)

Although these players paved the road before Ashe entered the tennis scene, he still had to overcome the overwhelming presence of prejudice and racism surrounding the sport. From being falsely accused of destroying property that other (white) players had actually destroyed, to being barred from playing in certain tournaments because of the color of his skin, Ashe’s path wasn’t an easy one.

An introvert in nature, Ashe took Dr. Johnson’s lessons to heart. He made sure his behavior was beyond reproach. Dr. Johnson taught him to confront racism with grace, though Ashe privately worried whether he was doing enough to help effect change. He also fought back against the racism he encountered by becoming one of the best male tennis players of his time – arguably, of any time.

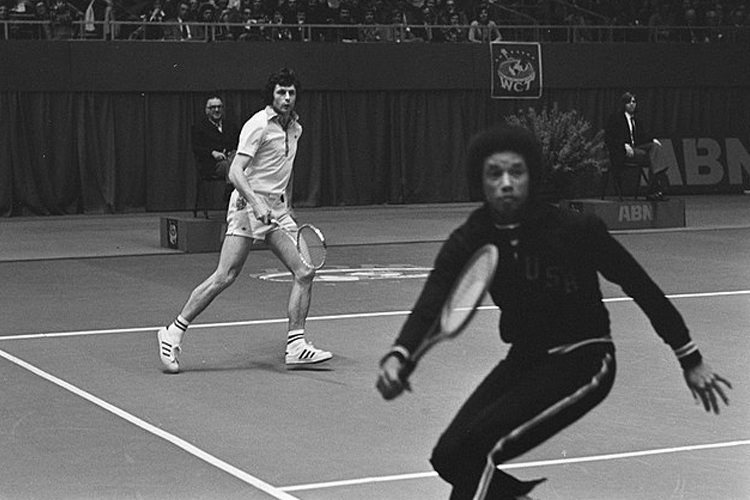

Ashe On The Tennis Court

Beginning at age 18, Ashe won the National Indoor Junior Tennis Championship in 1960, and again in 1961. That year, he also won the USTA Interscholastic Singles Championship. At age 20, Ashe was recruited by the United States Davis Cup tennis team, where he was the first African American in the unit.

By 1968, Ashe was a tennis amateur carving his way through the pros at the US Open. The odds of Ashe winning seemed insurmountable. He was a 25-year-old facing off against seasoned professionals, including his boyhood idol, Pancho Gonzales.

A string of upsets improved his confidence. The semifinal match against Clark Graebner was over after four challenging sets, and it was off to the five-set finals against Tom Okker.

When Ashe came out victorious, winning the US Open, his father joined him on the court for an emotional moment. Ashe had to forfeit the prize money to Okker despite beating him, because Ashe was an amateur player. Even so, the standing ovation from the onlookers confirmed that the world of tennis was ready to move away from the all-white tradition and become more colorful.

The confidence Ashe gained with this match, one of the most memorable of his career, served him well in his future games. Ashe continued winning championships, including three Grand Slams, and helped the USA to win five championships (1963, 1968, 1969, 1970, 1978). By 1975, he would be ranked as the number one tennis player in the world – the first African-American male to attain that achievement.

Ashe The Activist

Championship tennis not only brought fame, but it also paid well. As Ashe gained fame and fortune he didn’t self-indulge like other athletes. Instead, he used his name and money, along with his newfound confidence and social awareness, to speak out on civil rights issues.

Finally finding his public voice, Ashe refused to become cynical in the face of things that were wrong in America and around the world. He began engaging in political advocacy to fight unemployment and lack of proper education in poor inner-city neighborhoods. He also fought against apartheid in South Africa and marched in support of Haitian refugees. His later years were spent not only as a forceful activist, but also as a writer and philanthropist.

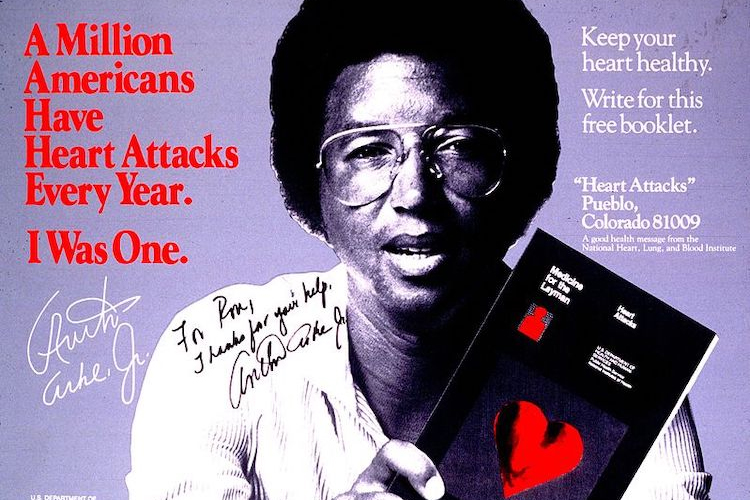

Big But Troubled Heart And HIV

Ashe had a big heart, and he was rightly troubled by global, social, and political wrongs. His health was also in danger – he underwent heart bypass surgery in 1979 at age 25, and again in 1983. The second surgery required a blood transfusion, one that passed on human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) from the donor.

Blood donation centers weren’t testing blood for HIV yet. That wouldn’t begin until 1985, in response to transfusions becoming a growing source of new HIV cases. Ashe’s infection went undetected until he underwent a brain scan in 1988 to address sudden paralysis in his arm. The biopsy found toxoplasmosis, a parasitic infection closely linked to AIDS, which was then confirmed to be AIDS, through blood testing.

Ashe tried to keep his diagnosis quiet, preferring to keep his privacy intact. He later said in his public announcement that he hated lying to everyone beyond his closest circle. But HIV and AIDS-related stigma was rampant, borne from the fear brought on by disinformation and lack of proper treatment availability. He only revealed the truth in 1992 after being informed by USA Today that they were going to run a story outing his condition.

Arthur’s Legacy

In 1993, Arthur passed away from AIDS-related pneumonia, just months before his 50th birthday. He lived in the Richmond Governor’s mansion in Virginia, the first one to do so since Stonewall Jackson in 1863. Over 6,000 people attended his funeral.

Ashe was a quiet trailblazer in tennis and an outspoken activist for the underdog. He was honored posthumously with the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1993 by President Bill Clinton, and in 1996, a statue in his honor was erected in Richmond, Virginia.